Charles Manson’s music was a macabre sidenote

Written by Live605 on November 21, 2017

Charles Manson, the cult leader of the Manson Family, who directed his followers to commit a string of brutal murders in 1969, was one of the most reviled figures in American culture.

A grifter who’d spent most of his adult life in jail, he orchestrated a killing spree with the intention of sparking a race war.

But his original intention when he arrived in California was to become a musician.

A macabre fascination with his music has persisted ever since. Bands like Guns N’ Roses, The Lemonheads and Marilyn Manson have covered his songs; while bootleg recordings of his demos, which began circulating during his trial, are now widely available.

Manson’s psychedelic brand of folk music was not, it has to be said, very good.

His guitar playing was basic, his lyrics disorganised, and his stylistic debt to The Beatles thinly disguised (sitar sounds are strewn across his recordings with wilful disregard).

Still, he made enough of an impression on his contemporaries to come close to securing a recording contract.

Manson, who learned guitar in prison, first arrived in California in 1967 and soon met prominent musicians including Neil Young, Dennis Wilson, and Doris Day’s son, the record producer Terry Melcher.

Young, in particular, was impressed by what he heard.

“He had this kind of music that nobody else was doing,” he told rock writer Bill Flanagan.

“He would sit down with the guitar and start playing and make up stuff, different every time.

“Musically I thought he was very unique. I thought he really had something crazy, something great. He was like a living poet.”

John Phillips of the Mamas and Papas was less enthusiastic. Asked on several occasions to record with Manson, the singer recalled: “I’d just shudder every time. I’d say, ‘no, I think I’ll pass’.”

Manson’s closest brush with musical fame came after Gary Hinman, a music teacher who would later be one of the family’s victims, introduced him to Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys.

Wilson took one of Manson’s songs, Cease To Exist, and turned it into the Beach Boys’ song Never Learn Not To Love – taking a full writing credit for himself, after changing some of the lyrics and adding the band’s famous harmonies.

Manson reportedly received a one-off payment and a motorcycle in exchange for the rights to the song, but he came to resent Wilson’s “theft”.

In a sinister preface to his later crimes, he left a bullet on the drummer’s bed.

“I gave Dennis Wilson a bullet, didn’t I? I gave him a bullet because he changed the words to my song,” Manson later told US TV presenter Diane Sawyer in an interview.

Manson perhaps restrained himself from taking further action because Wilson, as well as letting the Family stay at his house, had promised to introduce Manson to Melcher, who had assisted The Beach Boys on their Pet Sounds album.

The producer agreed to watch him perform at Spahn Ranch in May 1969 – but left unimpressed, declining to work with him.

After that, things quickly turned dark.

Manson became convinced that Armageddon was coming. He believed that the race riots of 1968 and the Black Panther movement were the start of a race war.

Increasingly paranoid, he gleaned what he believed were clues in the Biblical book of Revelation and the Beatles’ White Album, in songs such as Piggies, Blackbirds and Helter Skelter.

He staged his killings to make it look like they had been committed by black militants, naming his plan Helter Skelter after Lennon and McCartney’s song.

The first killing took place on 25 July 1969, when Manson sent three members of the Family to Hinman’s house. After being held hostage for two days, Hinman was stabbed to death.

On 8 August, Manson sent four people to Melcher’s house, with instructions to kill everyone they found. However, the producer had moved out, and film director Roman Polanski now had possession of the property.

The gang burst in and killed four people, including Polanski’s pregnant wife, Sharon Tate.

Despite the horror of his crimes, Manson somehow became a celebrity. While on trial, he carved an X on his forehead and relished his role as an anti-hero, ranting for the cameras, making crazy demands and threats.

While in custody, he asked Phil Kaufman, who he had met in a previous prison incident, to see that his music was released.

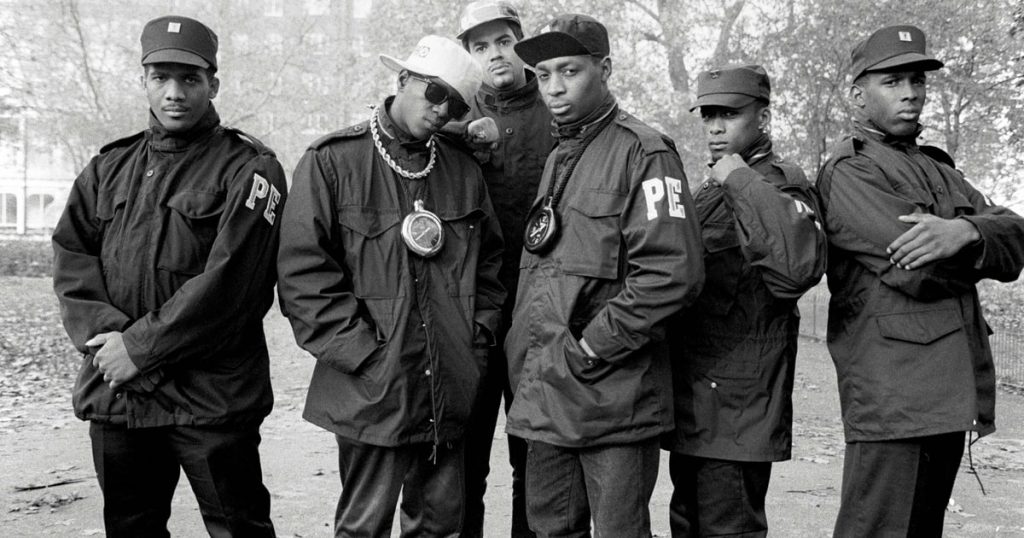

Unsurprisingly, no record label would touch the recordings – but Kaufman raised the money to get an LP pressed up, and it was distributed by Awareness Records, the same label that put out Bob Dylan’s The Great White Wonder, widely considered to be rock’s first bootleg.

The album was titled Lie: The Love and Terror Cult – a play on the Life Magazine cover of the same title from December 1969. In the 1970s and 80s, it became a collector’s item in the punk and metal scenes – and it is now widely available on streaming services.

There’s a morbid fascination with the recordings, and people search for clues to Manson’s horrific crimes in the lyrics.

Such clues are few and far between – but his language paints an eerily accurate picture of the methods he used to manipulate the members of his cult.

“Think you’re loving baby, but all you’re doing is crying… Are those feelings real?” he sings on Look At Your Game Girl, which “embodies Manson’s fundamental approach to influencing young women by targeting their socially imposed hang-ups and implying that his way is better and more liberating”, wrote music critic Theodore Grenier.

The ominously-titled People Say I’m No Good, meanwhile, is little more than a rant about society’s double standards, a theme that is echoed on Mechanical Man and Garbage Dump (which criticises food waste and advocates dumpster diving, years before it became a cause celebre).

So in the end, Manson’s musical ambitions amounted to nothing more than a footnote.

And while the likes of Marilyn Manson (who named himself after the criminal) sought to associate themselves with his evil acts, others came to regret it.

Axl Rose, who wore a “Charlie Don’t Surf” t-shirt featuring Manson’s face on Guns N’ Roses Use Your Illusion tour, later sought to distance himself from the cult leader, donating profits from a cover of Look at Your Game, Girl to charity.

“I wore the t-shirt because a lot of people enjoy playing me as the bad guy and the crazy,” he said in a statement. “Sorry, I’m not that guy. I’m nothing like him. There’s a real difference in morals, values and ethics between Manson and myself … He’s a sick individual.”

But perhaps the best response to Manson’s musical aspirations came from Bono.

“This is a song Charles Manson stole from the Beatles,” he said, while introducing a live version of Helter Skelter on U2’s Rattle and Hum.

“We’re stealing it back.”

Information for this article was originally posted on The Guardian

SF News

SF News  Sunny Radio

Sunny Radio